The first time I tried to describe my characters, it was a total disaster.

The first time I tried to describe my characters, it was a total disaster.

I couldn’t understand why because I’m a very descriptive writer. Describing landscapes? I got that. Fantasy creatures no one’s ever seen before? You betcha. Medieval cities? I’m a pro.

But when it came to people, suddenly I couldn’t find any words that worked. No matter what words I used, the descriptions fell flat instead of bringing my characters vividly to life.

I didn’t realize then that I was going about my character descriptions all wrong—I thought I just sucked at describing people. Years later, though, I learned that anyone can write a stellar character description, even if descriptive writing isn’t their strong suit!

Any of this sounding familiar? Describing characters is something a lot of writers struggle with, myself included. Though I’ve come a long way since my first feeble (and horrible) attempts, it’s still something I have to work harder at than other types of description.

I don’t know if I’ll ever understand why people seem to be so tricky to describe, but I don’t want you to face the same frustrations and struggles that I did. You’re not alone, and I’m here to help, friend!

I’ve written this MONSTER guide to answer all of the most frequently asked questions about describing characters I’ve gotten from writers like you. I’ve also created FREE worksheets and cheat sheets to make describing your characters a whole lot easier, so be sure to grab those below! (No email sign-up required!)

Now, without further ado, let’s get into the why, when, who, what, and how of character description!

Now, without further ado, let’s get into the why, when, who, what, and how of character description!

What Is the Purpose of Character Description?

I feel like the purpose of character description often gets somewhat muddled in writers’ minds. If I asked you why you want to describe your character in your story, what would your answer be? You would probably say you want to give the reader a clear mental picture of what your character looks like.

That’s a valid reason, but there’s another that is even more important but sometimes gets overlooked.

The main way I use character description in my stories is as a form of characterization. Through descriptive details, I try to reveal the character’s personality so that not only does the reader come away with a mental picture of what the character looks like, but they also get a feel for who the character is.

Before I viewed description as an opportunity to characterize, I was hung up on the description itself. I thought character descriptions had to be beautiful and lush with detail. I felt a lot of pressure to find the right words so my readers would picture my character exactly as I did. I thought because I couldn’t write gorgeous character descriptions, I sucked at them.

But you know what I finally realized? Describing a character is more about characterization than flowery language. Once I realized this, a lot of the pressure I felt toward describing my characters lifted.

When Should I Describe My Character?

Whenever you introduce a new character, you should try to describe her as soon as possible. Why? Because the moment a character steps onto the page, the reader’s imagination will immediately begin to conjure an image.

For example, let’s say I encounter a character named Louise in a story. I immediately begin to picture a brunette woman in a retro dress, bright red lipstick, and fashionable glasses. Don’t ask me why, that’s just the image that springs to mind.

Now, this image may or may not match up to the author’s own personal idea of what she intends Louise to look like. If the author doesn’t give me any details to provide me with a different mental picture ASAP, I’m going to stick with my own version.

If you wait too long to describe your character, the reader will likely reject your description in favor of their own mental image. Let’s say you’re reading a story and you’ve been imagining the heroine as a petite girl with a blonde pixie cut, but halfway through the book you find out she’s actually 6 foot tall with waist-length black hair.

That discovery will be jarring to the reader. Since the read is already familiar with the mental image she had created for the character, she will likely ignore this description and keep imagining her the way she likes. I have done this several times myself as a reader!

To avoid this situation, try to describe a new character as soon as she’s introduced to provide the reader with the mental image you want them to have.

Now, there is one exception to this. If a character is introduced in the middle of an action scene, you do NOT want to bring the action to a screeching halt to describe them. Wait until things have calmed down, and then you can describe them. It’s okay to wait a few pages, I promise.

Which Characters Should I Describe?

You don’t have to give a detailed description of every character in your novel. You should give most of the attention to your main characters, and then add a little detail to your secondary characters.

You don’t need to describe the desk clerk at the hotel, the taxi driver, or the bartender. Some characters are just background extras that don’t have any importance in the story so you don’t want to spend any more time on them than necessary.

If you start describing these types of characters you call attention to them, and you could confuse the reader into thinking they might be important later when really they have no significance other than filler to make your story world feel fleshed out. So let the reader’s imagination fill in the blanks on this one, or limit yourself to a brief, simple description like “the burly bartender.”

I also want to point out that there tends to be a difference between how main characters and secondary characters are described. Secondary characters are often more colorful, exaggerated, and quirky. Because they have a small role, they have to burn bright to be memorable. So feel free to get crazy with your secondary characters and have some fun!

How Much Should I Describe?

The amount of character description really depends on the writer and their writing style. Some writers are really good at writing beautiful character descriptions, so they might make their descriptions longer. Other writers have a very to-the-point and less descriptive writing style, so their character descriptions may be very sparse.

I would say a paragraph of character description should be more than enough (with 3-5 sentences being one paragraph). Any more than that might start leaning toward too much, but it’s always a judgment call. A reader can only remember so many details and you don’t want to overwhelm them. Often, less is more.

Funnily enough, I don’t think there’s any danger in describing too little. In fact, some writers intentionally choose not to describe their characters at all. Now, you’re probably thinking, why in the world would any writer want to do this? Good question.

One argument for not describing your characters is to allow the reader full control over how they want to imagine them.

Remember how earlier we talked about readers immediately conjuring mental images for characters? Readers’ imaginations are powerful and very good at filling in the blanks. Some readers prefer to imagine things their own way and not be told how to image them by the author.

Another argument for this tactic is that when a character is left undescribed, the reader will often project their own physical features onto the character.

So if they’re blonde, they’ll likely image the character as blonde. If they’re Asian, they’ll likely imagine the character as Asian. This is why some authors prefer not to describe their heroes—so that the reader can imagine the hero looks like herself, no matter her physical features or race.

It’s a beautiful thought that one character could look so many different ways to so many different readers!

So really, it comes down to personal choice. When you have a specific image in your head of what your character looks like, it can be hard to relinquish control and let the reader imagine them however they want. However, if you want the reader to picture the character a certain way, then by all means provide them with that description!

But keep in mind that no matter how meticulously detailed your description is, your readers won’t recreate your mental image with 100% accuracy (and that’s okay!).

Words aren’t photographs, and that can sometimes be challenging and frustrating. This is why the best advice I can give you is to focus on characterizing with description instead of focusing on writing the most accurate description possible.

What Should I Describe?

Many writers have trouble moving beyond hair and eye color in their descriptions, and I get it. Those two things are the easiest and most obvious to describe. But what else can you say about a character’s physical appearance?

To create an effective character description, it’s all about 1) choosing the right details to convey personality, and 2) choosing the most interesting details. Remember, you don’t need to describe everything. You just need to describe the best things.

For example, depending on which details you choose to focus on, you could convey a wild character (spiked lime-green Mohawk, mermaid tattoo, wearing a live yellow boa constrictor as a scarf), a sloppy character (uncombed hair, wrinkled shirt, crumbs in beard), or a timid character (hunched posture, eyes cast downward, plain/muted clothing).

Notice how I only mentioned a few details but already you probably have a pretty good visual picture of these characters and a feel for who they are. It doesn’t take much! And these types of details tell the reader far more about the character than “he had jet black hair and blue eyes.” Ask yourself what this character is like, and how you can express this visually.

Here are some ideas of what you can describe to get you started:

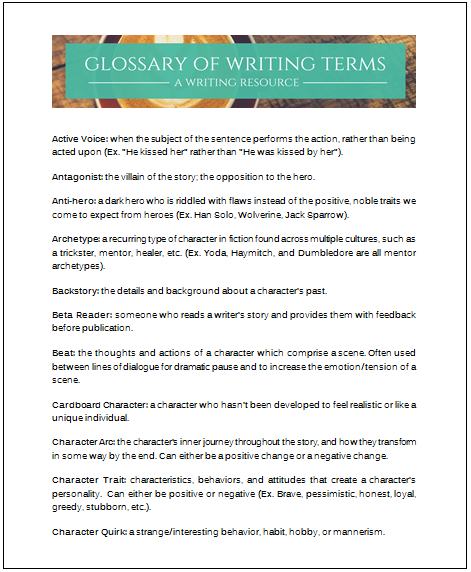

- Facial features (face shape, eyes, nose, lips, jaw, chin, brows, ears, cheekbones, facial hair)

- Hair color, texture, and style

- Build/body type and height

- Skin tone

- Skin texture (weathered, wrinkled, smooth, hairy, etc.)

- Skin afflictions (acne, eczema, oily, moles, warts, boils, etc.)

- Distinguishing features (scars, freckles, birthmarks, tattoos, piercings, etc.)

- Teeth

- Makeup

- Clothing, accessories, and personal items

- Voice/accent

- Posture

- Scent

- Gestures, body language, mannerisms

How Do I Describe My Characters? (Tricks for Better Descriptions)

1. Avoid Creating a Grocery List of Physical Traits

Don’t merely list out your character’s physical traits like you’re checking items you need off a list. It will end up sounding like this:

“He was a young man with brown eyes and black hair. He was tall and wore jeans with a red t-shirt.”

Blah! The problem with this sort of description is that it’s completely forgettable and boring. It doesn’t create a vivid image that brings the character to life. It doesn’t reveal anything unique or interesting about him. This description is far too basic; we need to go deeper to create a character that pops off the page. Read on to find out how!

2. Choose Interesting Details

As I already mentioned earlier, you want to choose interesting details about your character that show his personality. Don’t go overboard here—two or three should be plenty. One carefully chosen detail can say far more about your character’s personality than five or ten general details.

3. Use Similes and Metaphors

Using similes and metaphors help to give a more vivid picture and a stronger emotional impression about a character.

For example, instead of “He was tall” a better description would be: “His towering bulk loomed in front of her like a mountain, immovable and impassable.”

The first is just a stated fact. However, the second gives us the feeling that this character is formidable and might pose a problem or obstacle, and the imagery is much stronger.

4. Consider Perception

The description of a character can change depending on who is describing him. For example, a man’s wife will describe him far differently than his enemy.

Consider how your viewpoint character perceives the character being described, and communicate their impression through word choice and the details they focus on.

5. Get Specific

The more specific you can get with your details, the more vivid and interesting your description will be and the more it will reveal about the character.

For example, instead of “He had blue eyes” try, “His eyes were the same turbulent, depthless blue as the sea he had sailed upon since he was a boy.”

The first tells us nothing, while the second suggests the character is dealing with some sort of internal turmoil and also reveals he’s a sailor.

6. Add Movement

People aren’t still-life portraits. When you put your characters into action, it helps bring the description to life.

What is your character doing? Clutching nervously at her purse on a busy street? Tapping her foot as she waits in line for coffee? Hunching her shoulders and ducking her head as she walks through the school halls? Hot wiring a car? Dancing in the middle of the supermarket?

Actions help to reveal the character’s emotions, hint at what’s going on beneath the surface, and characterize her further. Try to incorporate body language, posture, mannerisms, and other actions into your descriptions.

Let’s Review

Now that you know the why, when, who, what, and how of describing your characters, it’s time to practice writing some descriptions of your own. It’s okay if your descriptions don’t turn out perfect at first—I promise the more you practice, the better you will become!

To help make things easier, I’ve created a collection of FREE worksheets for you to use. You’ll find cheat sheets that list physical details for easy reference and ideas, in-depth description worksheets to help you uncover the most interesting details about your character, and my 5 step no-fail character description template.

Click below to download + print these resources and get started! (No email required! It’s 100% free. Seriously.)

Key Takeaways:

- Describing a character is more about characterization than flowery language.

- When you introduce a new character, describe her as soon as possible before the reader creates and grows accustomed to their own image.

- You don’t have to give a detailed description of every character in your novel, just the important ones.

- Secondary characters often have more colorful, quirky descriptions to make them more memorable due to their smaller roles in the story.

- How much you describe is up to you. Some writers choose not to describe their characters at all so the readers can create their own images.

- You don’t need to describe everything about your character, you just need to describe the best things.

- Choose details the most interesting details that convey your character’s personality.

- Ask yourself “What is this character like?” and then express this visually

Additional Resources:

- 5 Simple Ways to Describe Characters

- 6 Simple Ways to Write a Physical Description

- Describing Character’s Clothing

- Describing Character Mannerisms

- Master List of Voice Descriptions

- Describing Skin Tones of People of Color

- 300+ Words to Describe Skin

- Great Character Descriptions From Fantasy Books

- Learn Character Description From the Pros (Examples of Descriptions)

- Face Claim Directory (Find photos that match your character’s description)