What was the setting of the last book you read? New York City? Dublin? The wilds of Africa? Outer space? Where did the author take you?

What was the setting of the last book you read? New York City? Dublin? The wilds of Africa? Outer space? Where did the author take you?

Now, let me ask you another question: Did the author succeed in taking you there?

Sometimes, I read books where the setting is such an integrated part of the story and so detailed that I feel as though I’m really there.

But other times, I’ll read a book that says it’s set in Montana but the setting is so empty that it feels as though it could be taking place anywhere. Or, even worse, I’ll pick up a book and have no idea where the setting is or forget where I’m supposed to be halfway through.

When we read, we love to be taken on a journey to somewhere new where we can experience that place and its culture without ever having to leave the comfort of our home. So it’s a shame that we writers often tend to neglect setting in our stories.

Maybe it’s because we’re overwhelmed with all the other details of plot and character. Or, maybe it’s because we don’t think that setting could be that important or make that big of a difference. But don’t be fooled–setting plays an important role in your novel just like your plot and characters!

What is Setting?

A setting is the place where the story’s events unfold. Novels contain multiple settings, which can be categorized a little something like this:

- Big picture location—the country, state, world, etc. in which your primary and small picture locations are contained.

- Primary location—where most of the story takes place.

- Small picture locations—additional settings where scenes take place.

Let’s look at a couple examples. First, from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone:

- Big picture location—The United Kingdom

- Primary location—Hogwarts

- Small picture locations—The Dursley’s house, the shack by the sea, Diagon Alley, Platform 9 ¾, the Forbidden Forest, the Gryffindor dormitory within Hogwarts, etc.

What about The Hunger Games?

- Big picture location—Panem

- Primary location—The Arena

- Small picture locations—District 13, the Tribute’s train, the training center, the Capitol, the cornucopia within the arena, etc.

When you’re trying to figure out your story’s setting, first start the the “big picture” location. This could be a real place like Russia or California, or somewhere fictional like Westeros or Middle Earth.

Next, narrow your focus to the primary location. Where within this big picture will most of the story take place? This might be tricky to pin down if your story is split between locations, or if you have multiple story lines with characters in different locations.

For example, in Lord of the Rings the characters are on a journey and visit a variety of settings along the way. And in Game of Thrones you have many different story lines with characters spread out across a number of primary settings like the Night’s Watch, King’s Landing, Meereen, etc.

After you figure out your primary location, start exploring other settings your characters might visit during your story. These will be both within the primary location, and beyond it.

When done well, setting will make a story colorful and memorable. This is because the author is creating a place that feels real and that the reader wants to return to over and over again each time she picks up the book. You don’t want your setting to be a blank in the reader’s mind because this takes away from one of the pleasures and expectations of reading—to be taken to another place.

You should treat your setting like you would treat any other character in your story. Characters need to be developed or they will end up feeling like flat pieces of cardboard. The same goes for your setting! Take some time to sit down and get to know your setting, researching or thinking about things like:

- The layout/geography

- What’s beyond in the outlying areas

- Politics, laws, and governing system

- Culture and traditions

- Weather

- Local plants and animals

- Jobs, economy, inports/exports

- History, enemies, and allies

- Folklore, urban legends, etc.

- Details only locals would know

- The hero’s feelings and opinions about the place

But now this brings us to the second point I wanted to talk about: worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding

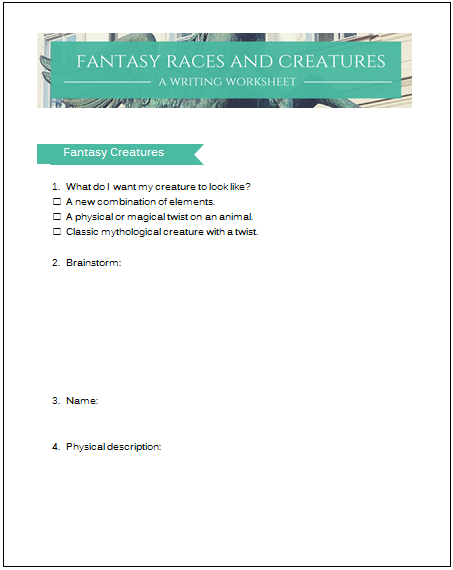

The term “worldbuilding” is usually used when talking about fantasy and sci-fi novels. It’s the process of creating a fictional world from scratch that still feels realistic. This process could include creating races, religions, histories, currencies, mythologies, cultures, traditions, and so on.

Worldbuilding is an important part of fantasy because the reader is being taken to an unfamiliar place that doesn’t exist. That means the author needs to make it feel realistic by weaving a web of details so complex that we begin to feel that there’s no way the author could be making this all up, that this place must really exist somewhere.

One example of fantastic worldbuilding is J.K. Rowling’s wizarding world in the Harry Potter series. Her attention to detail is phenomenal—she gives the wizarding world its own currency (galleons and knuts), sweet treats (Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans, anyone?), newspaper (The Daily Prophet), drinks (Butterbeer), transportation (The Knight Bus), and sport (Quidditch), just to name a few of the many details.

Rowling creates a world that is so fleshed out that you can become completely lost in it to the point where if someone came along and told you she made it all up, you’d probably call them a liar (let’s admit it, how many of us are still waiting for our Hogwarts acceptance letters?).

That is how powerful worldbuilding can be, when done well. But a word of warning: although you can get away without too much damage from lack of setting in most genres, in fantasy and sci-fi worldbuilding is critical to your story. It’s an expectation of the genre since readers turn to fantasy to be taken to a new, magical world. If you only have a cardboard world to offer, your story is going to suffer.

Worldbuilding Isn’t Just for Fantasy

Now, even though we mainly associate worldbuilding with fantasy and sci-fi, this doesn’t mean it doesn’t apply to other genres. There is an element of worldbuilding within any story you write. The only difference is, when the story is set in the real world rather than a fantasy world, we are working with fact rather than fiction.

What do I mean? To use my own hometown as an example, let’s say your story is set in Louisville Kentucky and your hero is a jockey who will ride in the Kentucky Derby. You have two worlds to explore and build here: 1) The physical setting of Louisville Kentucky and the Churchill Downs racetrack where the Derby takes place, and 2) The culture of jockeys and horseracing.

First, your physical setting. Whereas in fantasy you would make everything up, in this type of story you’ll need to do research to learn about the layout of the city and Churchill downs, the history of these places, famous landmarks, the climate of Kentucky, how the locals speak, and so on. You’ll also need to uncover details that will bring your story to life.

For example, there are details about my hometown that outsiders likely wouldn’t know. Like we’re very picky about how you pronounce Louisville (it’s Loo-uh-vul, not Lewis-ville or Looey-ville, in case you were wondering). And even if you’re a local and you’ve never been to the Derby, you still know that Derby hats and Mint Julips are a big thing because the local news will inevitably run stories on both of these every year around Derby time.

Your job as a writer is to uncover all these quirky little details to bring the setting to life. Every place has its own culture, and your readers want to experience it. These are the details that are going to give your setting character and make it stand out.

The second “world” you’d need to delve into is that of the horse racing culture, and also the life of a jockey. You would need to get the inside information about these worlds so they’re accurate and believable.

“Worlds” like this exist all around us, and everyone belongs to one world or another. For example, you and I belong to the “world” of fiction writing. We have our own lingo, jokes, processes, etc. that outsiders wouldn’t know. Your job is to bring the reader into whatever specialized world you choose so that by the end of the story, they feel like an insider.

Either Way, There Will be Work Involved

As you can see, it doesn’t matter whether you’re writing a fantasy, contemporary, or even historical fiction novel—there’s going to be a fair amount of work involved to develop a realistic setting, whether you’re making up all the details or researching them.

Having written both fantasy and historical fiction, I don’t know that one tactic or the other is really “easier.” With research it can be challenging to find the information you need, especially if you’re writing about something set in the past where you can’t visit the place at that time period or ask locals for inside information. On the other hand, creating an original, interesting fantasy world that’s detailed and realistic is no small task.

Whatever genre of story you write, take the time to put the extra effort into worldbuilding. Not only will help your story come alive and give your setting character, but it will make readers want to return to your book time and time again for a visit.

What books have you read that created believable, detailed settings that made you feel as though you were there? Tell me in the comments!

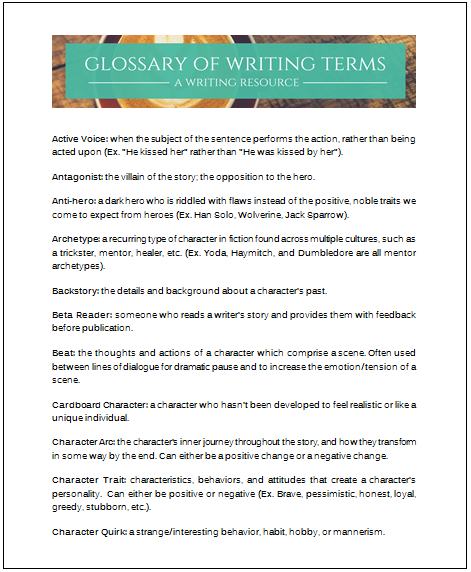

P.S. Behind on the Writing 101 series? Click to catch up! Part 1 (The Fundamentals of Story), Part 2 (Writing Term Glossary), Part 3 (Creating a Successful Hero & Villain), Part 4 (Unraveling Tension, Conflict, and Your Plot), and Part 5 (Let’s Talk Dialogue).

Ready for Part 7? Click here to read about Creating Effective Description!