Once, I spent a good three hours trying to fix a plot hole involving a parrot while writing my novella, These Savage Bones.

Once, I spent a good three hours trying to fix a plot hole involving a parrot while writing my novella, These Savage Bones.

I wish I was kidding.

There’s nothing that can make a writer want to tear their hair out quite like a plot hole. They can be hard to spot and even harder to patch up. And in the case of a particular species of parrot, which turned out to be extinct during the time period my story was set, they can make you question your sanity.

Argh, headaches for days!

Are there pesky plot holes hiding in your story right now? Let’s take a look at the different forms plot holes can take, how they can be accidentally introduced into a story, and how to rid your novel of them for good.

What is a Plot Hole?

Before you can fix your novel’s plot holes, you must first have a clear understanding of just what a plot hole looks like. Funnily enough, Wikipedia (of all places) has one of the best definitions of a plot hole I’ve come across:

“A gap or inconsistency in a storyline that goes against the flow of logic established by the story’s plot. Such inconsistencies include such things as illogical or impossible events, and statements or events that contradict earlier events in the storyline.”

So, a plot hole is a contradiction or inconsistency found within your story.

Why Are Plot Holes so Bad?

The problem with plot holes is that they can shatter the reader’s belief in the story you’ve woven. You know that feeling you get when you’re completely lost in a book? During that time, you forget about the outside world and the story’s setting and characters become real to you.

When readers become aware of plot holes, it jerks them from that fictional dream. It ruins the magic of the story and makes them realize the book in front of them is indeed fiction and not real. The plot hole becomes a distraction, and the reader may even begin to look more critically at your novel and try to find more inconsistencies instead of just enjoying the story.

The other problem with plot holes is that they make you look bad as an author. Readers will think you’re sloppy, or that you didn’t bother to think through the logic of your story. Plot holes can be embarrassing mistakes.

Examples of Plot Holes

So how can plot holes appear in your story? Let’s take a look at some examples.

Inconsistency: Let’s say in chapter one you introduce your hero who is a left-handed warrior. But in chapter 8 he’s wielding his sword with his right hand. Or, in book 1 it took your characters 10 days to get from town A to town B. In book 2, it only takes them 3 days. Whoops.

Contradiction: Let’s say you’re writing a fantasy story and early on you established that wizards can only use magic with a wand. But halfway through the story one of your wizards casts a spell with a wave of his hand. This directly contradicts the rules of magic you set earlier in the story.

Illogical: Let’s say your hero has magical fire powers. She has just been kidnapped and is tied up. She manages to find a shard of broken glass nearby and slowly saws through the ropes around her wrists to escape.

But why doesn’t she just use her fire powers to burn through the ropes in the first place? Sawing through the ropes might create tension in that scene, but taking advantage of her powers is the more logical choice for the character in that situation.

Factual Error: Let’s say you’re writing a historical story and your hero arms his fort with cannons to fend off the bad guys. But the problem is your story is set in the 12th century and cannons weren’t invented until the 13th century. Uh-oh.

Impossible: Your hero falls off a 100 foot cliff and survives. Or he becomes a master swordsman in a few days. Or he jumps out of a plane and falls up instead of down. You get the idea. If it defies the laws of science or human capabilities, it’s going to create a pot hole.

How Do Plot Holes Happen?

Now that we know what a plot hole is and have looked at home examples, you might be wondering how they can occur in the first place. Here are a few ways a plot hole can creep into your story:

Losing track of details. A lot of times a plot hole is created simply because the author forgets a detail of the story. This mistake is understandable—there can be an overwhelming amount of details you need to keep track of in a novel, and it becomes even more challenging if you’re writing a series!

Going back to our earlier examples of inconsistency and contradiction, both of these plot holes could have been avoided if the author had been keeping a close eye on the details.

Not setting clear rules and following them. If you’re writing a fantasy story, you need to set rules about how your world works and then follow them. If you don’t set rules, you’re likely to create contradictions and inconsistencies later in the story.

Not thinking things through. Sometimes plot holes happen because the author fails to look at all the angles and think things through. Usually in this sort of situation, the writer is more focused on making things exciting or interesting instead of paying attention to the logical, natural actions the characters would take in the situation.

In our example of an illogical plot hole above, this could have been avoided if the author had put themselves in the character’s shoes and asked what the character would logically do to escape.

Lack of thorough research. Whether you’re writing a medical drama, historical romance, or detective thriller, if you don’t do careful research you’re likely to create plot holes.

Not every reader might catch these mistakes, but some will. If a nurse reads your medical drama and realizes you have no clue about surgical procedures, she will either become frustrated with your book or laugh at you.

Lack of explanation. Sometimes plot holes are created simply because the author neglects to explain something.

Let’s go back to our earlier example of our tied-up hero with the fire powers. The reason she has to use that shard of glass to cut through the ropes is because the bad guys have used some sort of special fire-proof ropes so she can’t use her powers to escape.

But the author neglected to mention this so the reader is left to wonder, why doesn’t she just burn through them?? This leads them to believe there’s a plot hole.

Lack of set-up or foreshadowing. Have you ever read a book or watched a movie where something seemed to come out of nowhere? Two characters are suddenly making out and you didn’t even realize they were attracted to each other. Or the hero is lucky enough to find that gun under his bed when the serial killer is about to murder him.

Situations like these can feel like an inconsistency or contradiction in characters or plot. Where did that gun come from? Why are these two characters in love all of a sudden?

To prevent these sorts of things from feeling like a plot hole, you need to foreshadow or set them up earlier in the story before they happen. Show the characters flirting. Show how the gun got under the bed. Then your reader won’t call into question your consistency or logic.

How do You Find and Fix Plot Holes?

Some plot holes you may discover as you write your first draft, but most you probably won’t notice until you get into editing. The more time you spend with your story the more familiar you will become with it, and the easier it will become to spot plot holes.

Get to know your story inside out. Then, learn to look at it with a critical, careful eye. Think through your scenes and story details and look at them from different angles. Are they logical? Are they consistent? Do they make sense?

I also highly recommended getting another set of eyes on your story. Beta readers will come to your novel with a different perspective and will be able to spot plot holes you may have missed.

If you do come across a plot hole, try asking the following questions to begin brainstorming a solution to fix it:

- How much of the story did this detail effect? How much will I need to change? (i.e. the ripple effect)

- Can I simply remove this detail completely?

- Can I change this detail or replace it with something else that makes sense?

- Do I need to add, remove, or change something else in the story for this detail to work?

- Do I need to provide more explanation? Can I explain away this detail to make it work?

- What would my characters naturally do in this situation?

- Do I need to set up or foreshadow this detail earlier in the story?

Keeping Track of Your Story’s Details

Another way to find and fix your story’s plot holes, or avoid creating them all together, is to keep track of your story’s details.

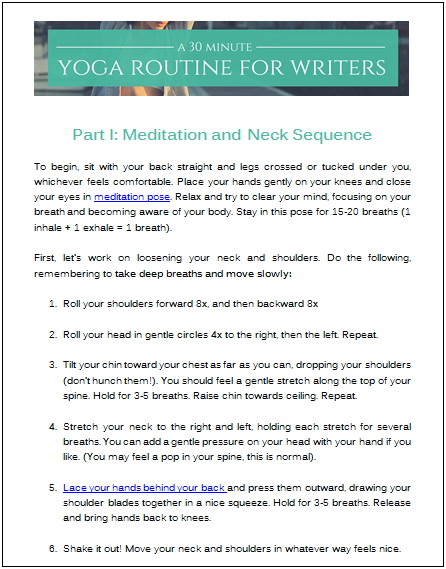

Years ago, I spent some time volunteering as a script supervisor for a local film company. What is a script supervisor, you ask? Well, the script supervisor’s job is to make sure there are no continuity errors in a film.

Every day I would closely observe the scenes as they were filmed with my continuity log in hand, taking careful notes.

So, for example, at the beginning of a scene I might take notes on where all the props were before the actors touched them. If we had to do another take or switch camera angles, my notes would be needed to return the props to their original positions. Sometimes, photos would be taken in addition to the notes.

This would prevent inconsistencies between camera cuts in the final version of the film. So let’s say two characters are talking and there’s a gun on the table. The camera cuts to character #1, who is now holding the gun. Then the camera cuts to character #2. Then the camera cuts back to character #1 who reaches for the gun.

Um, wait a minute, wasn’t he just holding the gun a second ago? Yep, he was. The script supervisor’s job is to prevent continuity errors like these through the meticulous notation of details.

To avoid inconsistencies and plot holes, you must become the “script supervisor” for your novel and be obsessive about details.

To help you out, I’ve created a free worksheet for you inspired by a script supervisor’s continuity log. You can use this worksheet to go through your novel scene by scene during the writing and/or editing phase and note all of your story’s details to make sure they stay consistent and logical.

Grab it here:

Let’s Review

- A plot hole is a contradiction or inconsistency found within your story.

- They ruin the experience of getting lost in a story for the reader and can make you look sloppy or lazy as a writer.

- They can take different forms: inconsistencies, logical fallacies, contradictions, factual errors, and impossible events.

- They can occur in a number of ways: losing track of details, failing to establish rules, failing to think things through, lack of research, lack of explanation, and lack of set up or foreshadowing.

- Getting to know your story inside out and learning to look at it critically will help you uncover plot holes. Beta readers can also spot errors you may have missed.